To an award show that's famous for honouring artists belatedly, we have sent as our official entry one of our major film-makers's weakest work yet, feels Sreehari Nair.

So I am taking my evening walk. The phone rings. It's the editor.

"First off," he says, his gruff tone leaning towards the paternal, "please ask your wife and kid to be extra cautious. The second wave is coming, and I am told it's going to be deadlier than the first."

His words carry a peculiar Christian weight. He utters the term Second Wave with the same gravitas that a priest might use to announce the Second Coming.

But this is 2020, Corona is the New God, and I absorb his words with utmost seriousness.

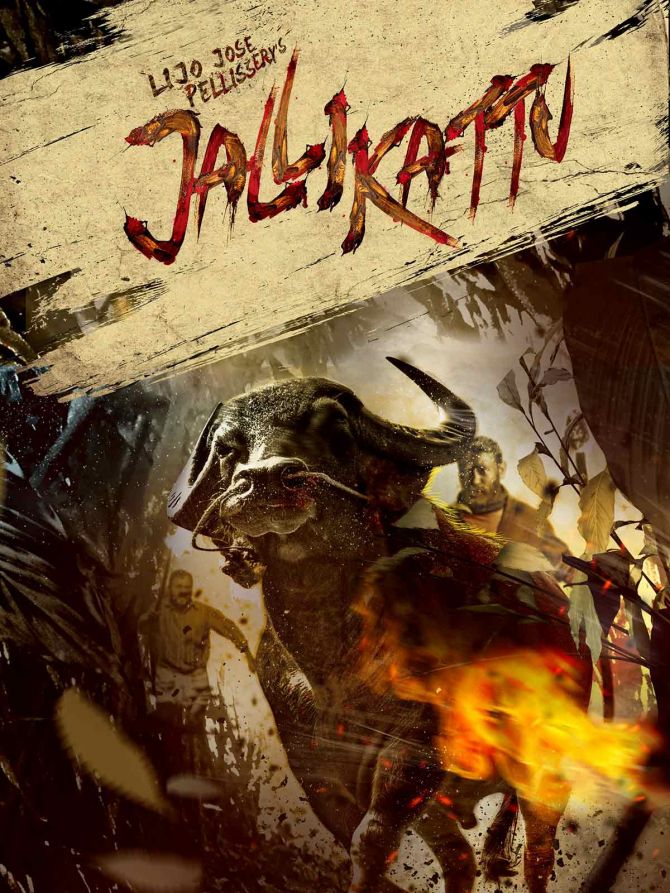

"Also," he says, "did you hear about Jallikattu being selected as India's official entry to the Oscars?"

I get ready to tell him that I am not keeping up with the developments on that front, but he cuts in. "I think you should write something about the film's chances."

"I saw some early posters," I say, "and did not feel like watching the film."

"Then, perhaps, you should write about why it's not the right pick for the Oscars," he says, and while I am thinking of a suitable retort, he adds, "and this is not one of your advertising gochigiris, where you take three months to sell one sachet of shampoo. This is journalism!"

He knows my tender spots.

Knows how to appeal to my father complex.

Knows, most of all, how much pause I should be allowed.

And so, while I perform mental gymnastics, he asks me, "So, by when can I expect the piece?"

"I'll watch the film tonight. And then, get cracking on the piece."

"Fine," he says, and disconnects the call.

Knowing that I have no practical way to express my defiance, I go on to complete 10 rounds of the park.

If I can't turn down his assignment, I'll turn down his advice asking me to be cautious, I say to myself -- the slavish contributor silently protesting his autonomy!

My apprehension about taking up this particular assignment has two sources.

Number one. I don't care anymore how a film fares at an esteemed awards ceremony/festival.

I don't care if it gets an official selection, I don't care if it’s nominated, don't care if it wins.

This is not to suggest that I think these ceremonies are rigged.

It's just that, in a hyper-connected world, of the sort we today inhabit, a film's performance at the Oscars, or Cannes, or Sundance, is largely a function of the opinions aggregated by the film even before its first showing, and has very little to do with an audience's or a jury's immediate, sensuous response to the work at hand.

Prestige is more important than merit in such cases, and any film that answers the question 'how do we make the world a better place?' is, for some reason, viewed as more prestigious than the rest.

Making it to, or making it big with the festival audience, is, at this point in time, not very different from making it to The New York Times bestseller list.

Posterity wouldn't judge a film by the trophies it scoops up at these ceremonies, just as it hardly matters now, what the weekly rankings of Roth or Bellow or Updike were when their books first hit the stands.

The second source of my apprehension overlaps with the first and has something to do with what I had mentioned to my editor.

I, who loved Lijo Jose Pellisery's Angamaly Diaries, loved his Ee. Ma. Yau. for the most part, was left underwhelmed by the first look posters of Jallikattu, out of which shone a too-evident desire to overwhelm me.

In Angamaly Diaries, you see two gangs fighting unto death, and then -- like the aristocratic aviators in The Grand Illusion, fighting on opposite sides -- become comrades.

One of the two gangs agrees to the peace accord out of desperation, the other agrees for purely economical reasons, and even as we are apprised of this fact, we get the humanity of the people involved -- a humanity that is never overstated.

The whole film expanded our understanding of its characters, and showed us that people are more surprising than we take them to be.

The posters of Pellisery's Jallikattu, however, beaming with the suggestion that the line between men and animals is fast vanishing (or something to that effect), were, I thought, quite self-congratulatory.

My grouse was, on some level, also personal.

It had to do with Pellisery's decision to turn his focus away from probing the Malayali Character and toward becoming a babe of the international festival circuit. I knew the posters would be seen as 'deep', but I wondered if Pellisery's this extreme anxiety about tackling (supposedly) universal themes was such a wonderful development.

And so, I made it my mission to avoid all of Jallikattu's publicity material, avoid watching the film, avoid reading the reviews.

The only bit that I remember looking at closely was a screenshot shared on a WhatsApp group.

It was a random shot from the film, featuring one of its characters, captured presumably after a lovemaking session, for it showed her nipples jutting out. A friend had shared the picture with the following caption: 'LJP and his eye for detail.'

Even to this last bit of temptation, I didn't succumb.

After holding out heroically for many months, I was now being made to watch the film.

And now that I have watched it, I don't know if I should be happy or dejected about reporting that my forebodings relating to Jallikattu weren't misplaced after all.

Remember the slobs in Amen and how they were treated almost like mythic figures?

Remember the dying man in Ee. Ma. Yau. and his last night of living it up?

Pellisery is a genuinely anomalous talent whose eye can lend, to even the goofiest acts of his characters, a certain ritualistic intensity; Jallikattu is what happens when such a talent assumes a saintly, professorial air.

I think this is India's way of holding a mirror up to the Oscars and its many blunders of the past.

To an award show that's famous for honouring artists belatedly, we have sent as our official entry one of our major film-makers's weakest work yet.

The village of Ee. Ma. Yau. had, by the end of the film, turned into a loveless setting whose occupants were shown as incapable of intuiting each other's pain and suffering.

Jallikattu is set almost entirely in a cannibalistic universe, occupied by madmen.

We are in Rubber & Beef Country, Kerala, where a buffalo has escaped from a slaughter house. And Pellisery spends close to two hours explaining to us that there is little that separates the scampering animal from the human beings who pursue it.

But the buffalo comes out better.

Way better.

In its scampering, you get a sense of its nervous energy, its will to live, and you can preview in its animatronic eyes, a tinge of sadness even.

It's the humans who are given a short shrift.

Defined in monochrome terms, you don't get to feel the hunger behind their gluttony, the heat behind their violence, or the yearning behind their sexual explosions.

The hypocrisies of people are magnified for us to catch; our great tragic ironist is fast turning into a rather simple-minded ironist.

The 11-minute-long unbroken shot at the end of Angamaly Diaries drew its power and its beauty from the way it crystallised in our mind, the various characters in the film, characters who were, up until that point, scattered in our memory.

Jallikattu, on the other hand, is a series of long-takes, of mostly people running, and you end up knowing as much about these runners as you did about the ant-sized soldiers in Kurosawa's Ran.

The desire is to be expressionistic, but once the buffalo slips away, the film feels mounted like one of those social and political satires you see on television -- fast blackout sketches, each sketch in search of the same ironical point: Men, and their intentions, are to be doubted.

What's good?

As it is the case with Pellisery always, each frame bustles with energy; each frame is vivid and active.

You can feel the director's pride, in making people and things move, and, in moving with them.

When Santhy Balachandran's Sophie steps out of her home, and, adjusting her hair tends to her chickens, the pepper and rubber trees in the background thresh in their full-grown thickness.

Surrounded by its hypocritical, self-centered, soulless inhabitants, however, even the greenness of the land is a kind of grief.

Also, interspersed like Cheeverian nuggets, throughout the narrative, are the folk realities of High-range Kerala: Jeeps fitted with leviathan loudspeakers, tea shops with steam billowing out of eateries fresh off the stove, hairpin curves that stretch endlessly, and churchyard trees from whose branches hang meat-filled black polythene bags.

What we miss are the great voices, so necessary to sustain a subject matter like this one.

The script, by S Hareesh and R Jayakumar, has no dramatic centre, or any room for memorable characters; instead, Pellisery gets his film-making juices running, he gets his people running, and the movie climaxes in the imagery of them falling on top each other while still in their strides.

There’s one arc that, to some degree at least, breaks away from the modern existential agony.

This arc concerns a long-running feud between Anthony (Anthony Varghese) and Kuttachan (Sabumon). Anthony is a boy-soldier who dreams of becoming the king of the hills, while Kuttachan, on account of having been a legendary figure of the hills once and someone whom the hills later banished, now spends his days attending to his fatalism.

When the buffalo goes amok, and the villagers bring back the rifle-wielding Kuttachan, the stage is set for the two men to prove their manhood.

All through the movie they keep running the animal close but never quite manage to grasp it by the horns. And this quest of theirs parallels their vying for the affection of Sophie, who’s a world-class tease, just as elusive, and herself a force of nature.

The cast, which also includes Chemban Vinod Jose and Jaffer Idukki, deliver solid, serviceable performances, but none of the performances develops into anything substantial.

It is only the reedy, pissy-looking Jayasankar Karimuttam, appearing in just one scene, who leaves a lasting impression.

Karimuttam plays a tea shop owner who doubles as the unofficial historian of the land and its people.

The actor takes his lines, adds to them humming and grunting noises, his mouth always at the edge of swearing, and the inflection in his speech a measure of the frustration that's rising and falling inside him.

Karimuttam appears early in the movie, but his rough argumentative tenor stays with you till the end.

The characters in Jallikattu are either erupting in anger, or talking over somebody, or screaming down somebody else, and yet, the loudest voice in the film is undoubtedly Lijo Jose Pellisery's.

The director -- who was once given to planning everything down to the last detail -- has, since Angamaly Diaries, been adopting a looser, more instinctive approach to shooting his pictures.

Consequently, the process of making his films has slowly become the dominant subject of his films.

Jallikattu's standout performer is Pellisery.

It is his show.

After you have watched the film, all you might find yourself talking about are aspects such as his ingenious way of lighting a scene, using, among other things, burning torches, and the headlamps he straps to the foreheads of the sprinting men.

Or you might talk about his decision to mix natural sounds with A Capella, and how that gives the film the texture of a ballad.

But the theme that is driving the ballad is what rankles this time. It is too predictably maudlin, and it doesn't allow the numerous technical flourishes to coalesce.

'Men are wild beasts' is the kind of idea that you can project onto just about any gruesomely detailed newspaper story, knowing very well that the idea will light up the story.

It's that all-purpose, that reductive an idea.

This symbolic ranting against the soullessness of all things was what marred the last act of Ee. Ma. Yau. as well, and what, I suppose, prompted a reviewer who loved the film to assert that 'it is tinged by the recognition that whatever the circumstances, human beings will continue to be petty and selfish and greedy.'

Believing that these qualities are what define human beings is to believe that we are essentially morons or humanoids, and the line of thought is as sentimental as the we-are-all-one-big-happy-family thought propagated by the films of Rajshri Productions.

I must add, also, that it doesn't take much imagination or talent to turn any everyday event into a symbol of 'the degradation of society' and 'the erosion of our values'.

My huffy walk, when asked to write this piece or my friend's posting of the nipple-shot, are these, anything more than instances of sad comedy that make up most of our brief lives?

Leave it to LJP, however, and he might tell you that these are signs that the human race is regressing back to its pre-civilisation state.

In his best films, Pellisery, without getting bogged down, conveys his love for the corrupt milieu of his stories.

In Angamaly Diaries, he stood very much with the hoodlums.

But in a film like Jallikattu -- or, as the trailer of his upcoming Churuli suggests -- even his close-ups reveal an indifferent eye for human frailties (The film festival eye, perhaps?).

Having left the human garden, and having ascended the spiritual stratosphere, Lijo Jose Pellisery, with his bearded, saintly look, now seems to be watching us all from up there.

God help us lowly creatures!